With famous Russian artist Pavel Nikonov

With famous Russian artist Pavel Nikonov

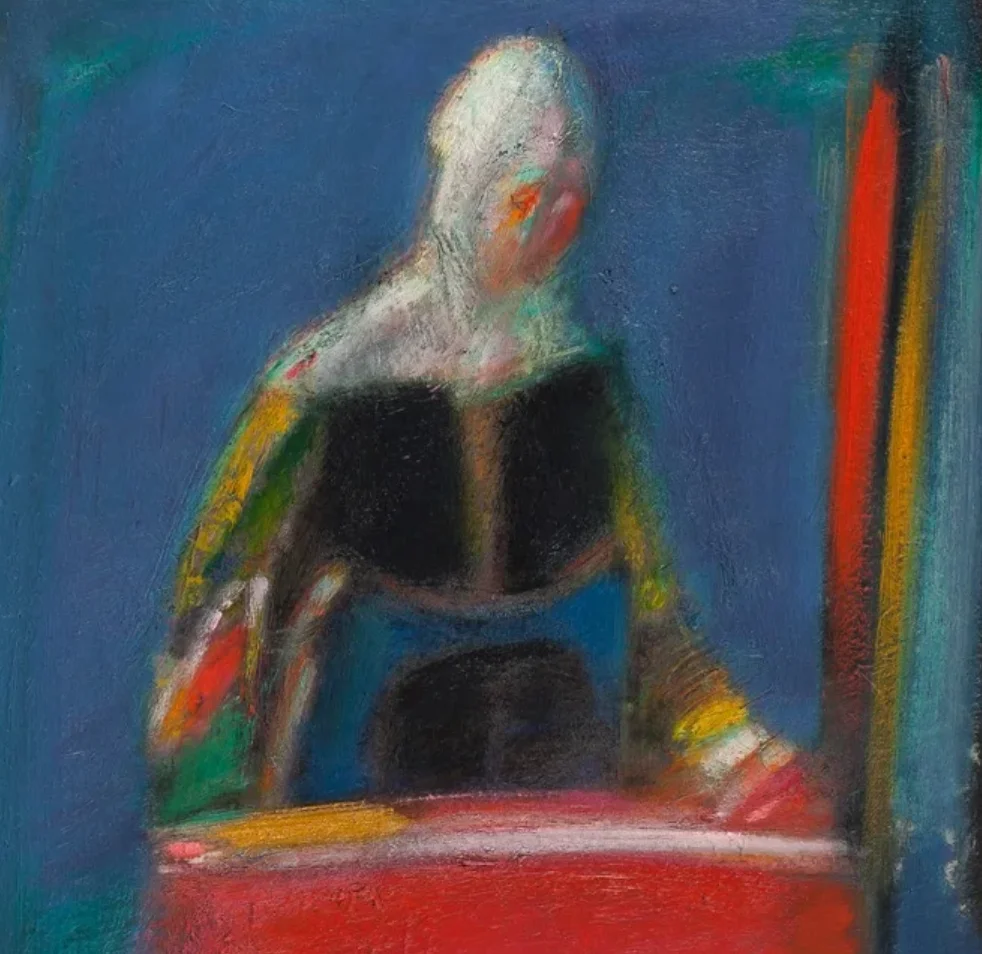

Yerbolat Tolepbay’s exhibition at the National Museum of Astana in 2017 is dedicated to the 100th anniversary of his mother’s birth. The artist has reverent feelings for the woman who gave birth to him and happiness to many people.

Uldar-apa was a known healer in the south of Kazakhstan. She was loved and respected by all who knew her. A vivid memory of the artist’s childhood is a crowd of people who came to ask for help standing in the yard of their house. They had different family, personal or health problem. Uldar-apa got tired but never refused to help. She always had the table laid and different people, very often strangers, sat at it. The boy’s world was shaped by impressions of these meetings with people – both known and unknown to the family, so different and so similar. This world turned to be connected with a man’s fate.

This was how the perception of life, with all its different forms but invariable essence, evolved in childhood.

Having become an artist, Yerbolat Tolepbay sought to express his experience visually.

His paintings grow one from another into a chain where each link is a step towards understanding the diversity of being. People in their pursuit of happiness, in their best and worst manifestations, have become the main object of the artist’s creative research.

His characters may be immersed in the pool of social conflicts, discrepancies and vain expectations. Or, they may belong to a world of ideal soulfulness and spirituality the artist endows life in the steppe. Yerbolat had different periods in his work, in his search for and exploration of changing plastic forms, but his main idea in the expression of the essence of being remained unchanged.

These worlds were depicted differently, in different stylistic manners. In Yerbolat’s complicated compositions his characters of the present and the past are given equal importance and each of them has their special life space. To express existential controversies that are inevitable among human beings, the artist connects the opposites: the East and the West, traditions and innovations, figurativeness and abstraction, narrative and the lack of subject. Interconnected by the artist within the space of a painting, all these things create a vast area of associations appealing to the viewer’s imagination.

In Tolepbay’s works, national traditions connect with modernist views. In his abstract paintings colour becomes an analogue to emotions and feelings. The vibrant mosaic can turn into narrative. The artist conveys the dramatism of a conflict situation with the same ease as the atmosphere of cosiness and harmony of hearth and home, or the endless vastness of astonishing Kazakh landscapes – the steppe and hills in their inseparable wholeness.

When childhood memories awake, along with thoughts about the steppe life, the artist turns to minimalism. Balancing on a thin edge between reality and metaphysics draws him away from specificity and the need to be “literal” about hallmarks of the reality.

Then the poetry of stylisation emerges: excessive details stop existing, figures are given only contours, colourful clothes and frozen movements, and the world has the colourful surface leading to farness. The combinations of bright spots with tender gradient transitions signify the simplicity of an occasion and nuances of the state of soul. What is seen is transferred into feelings. The departure from direct interpretations endows things and events with symbolic properties and subtexts. As a result, simple things such as, for example, a swing or a jump rope that allow us to get off the ground for a moment become a symbol of free flying.

A yurt doorway appears in many paintings as a symbolic portal to another reality. The door divides the painting into two parts, making it possible to be present within and outside a yurt at the same time. Finding themselves in two different spaces at once, a viewer comprehends symbolic meanings through the images of the physical world. A typical feature of the artist’s characters is their complete immersion in the self, even if they are united by a common action. One of the artist’s favourite motives is a dancing dervish – the absorption by the dance, the plasticity of hands jerked in the air, the mystical spinning. This is a painted meditation, a departure from reality to a world where only music that directs movements and consciousness and that is expressed in colour exists.

A key image in Yerbolat’s works is a woman in her different manifestations. She may be a na?ve small girl, or a lovely young one, or a woman. She is always occupied with work, or harvesting, or playing with a child, or talking to a friend, or having rest, or going for water, or sewing. Whatever is her occupation, she is always beautiful: a bowing girl on a camel fascinating with her beauty and grace, a pregnant woman in the state of sacred waiting and the entire world inside her, or a mother who gave birth through the divine energy of love.

Not long before she passed away at the age of 85, Yerbolat asked his mother, “Was your life long?” Uldar-apa answered, “Balam [my child], my life passed like it was only five days. I remember myself as a girl on the first day. The second day is when I got married. The third one when I gave birth. On the fourth day, my first grandson was born. And my fifth day is this one, when I talk to you.”

Yekaterina REZNIKOVA

Candidate of Arts