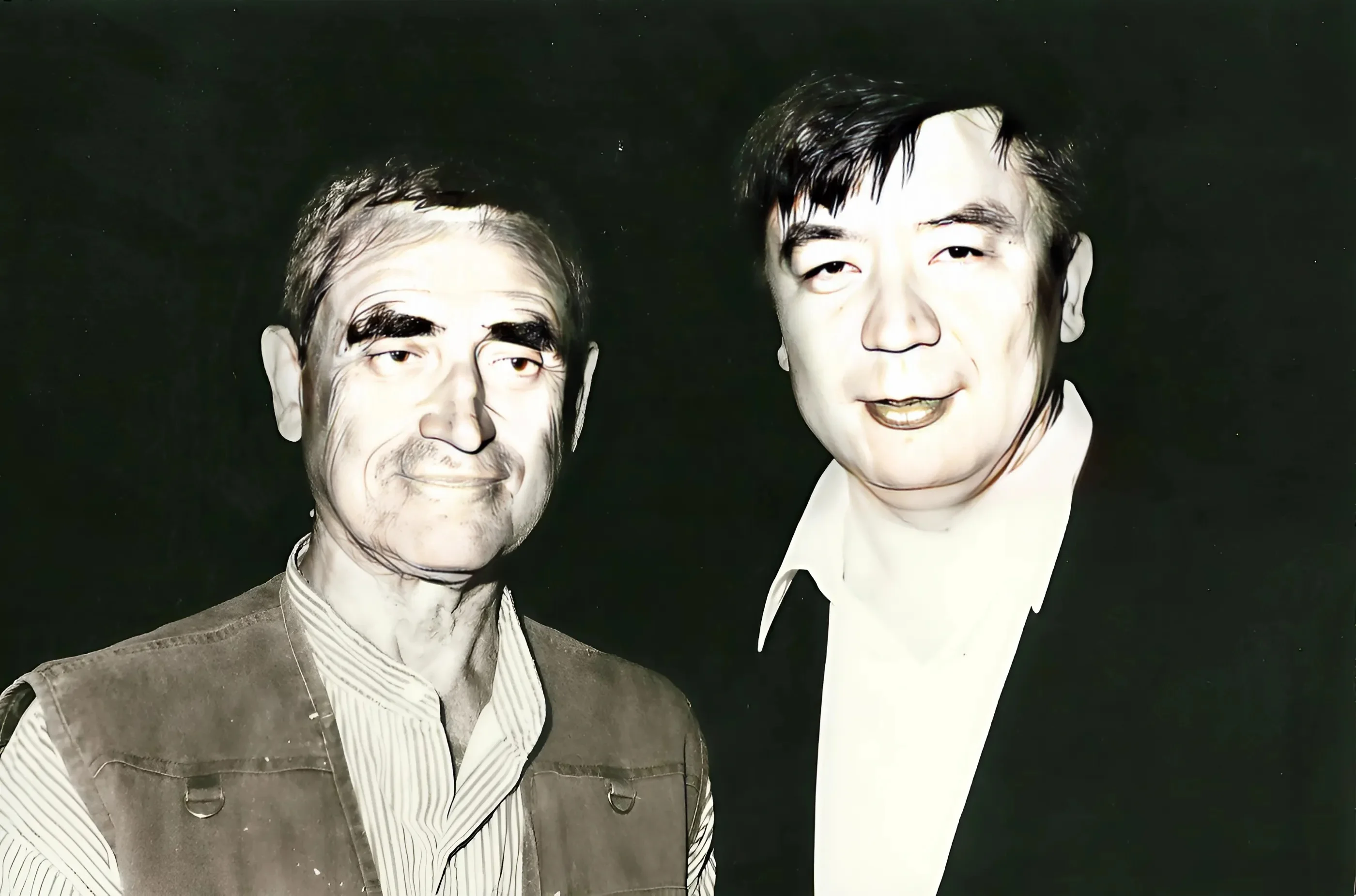

In the workshop at work

In the workshop at work

Yerbolat and I are of the same age. For some reason, there are very few of us who were born in the 1950s. In Kazakh art, at least, all are either older by ten years, or younger. In 1980, we were 25 and the time was extremely boring: communist party sessions, empty food stores, and a longing for jeans.

There were many exhibitions, however. Museum workers went to vernissages at the Union of Artists and artists visited the museum.

In between, they met at workshops. Yerbolat had a splendid one, with a “rest corner” he had built on his own and, as he joked, a place to erect a fountain. At that time, it was really a joke. He was already famous among a narrow circle of artists and critics after having displayed his A Farewell to Turksib Builders at a young artists’ exhibition in 1982. The work impressed everyone, even the most venerable artists. First, it astonished with its monochromatic colours: it was believed then that a painter should demonstrate his ability to show highlights and reflexes or, at least, paint in “open” colours like the Sixtiers had done.

Yerbolat’s palette included only ochre transitions into grey and back and a haze of white in a cloud. Second and most important, it conveyed the feeling of hopelessness, perplexity and incomprehensible sadness. In the end, this was a “farewell” not to those going to a war, but to those who departed for an all-Union construction project. These occasions were usually depicted as a great event, with flowers and a brass band.

We all knew Abylkhan Kasteyev’s colourful Turksib of 1966 where shepherds on horses marvelled at a “steel horse.” We surely remembered Ilf and Petrov who, in the dog-eared The Little Golden Calf, compared a steppe Kazakh and a Japanese graduate of Tokyo University and Oxford who looked the same.

It was only in 2016 that we watched the forgotten documentary Turksib filmed by Victor Turin in 1929. It was half-prohibited during the Soviet times and it is now clear why – the problem was not in the Yerbolat and the 1980s struggle between people and the elements, as official film critics wrote, but in the tough

invasion by gear of the steppe and the use of slavish handwork of the locals, which later shaped the classical picture of Soviet construction projects, including the Volga-Don Canal, Magadan, Norilsk and Brezhnev’s useless BAM.

In the picture, a farther and a mother, who saw their son off, stay alone with their yurt, a melody of a dombra and a mausoleum. They know he won’t be back, for various reasons.

The aching void conveyed by the father’s round-shouldered figure and the despair showed by the mother’s back express no certainty that their son’s path will be associated with Oxford anyhow.

By the way, Yerbolat, as A New Child in a City (1981), visited Paris, Istanbul and Barcelona, if not Oxford, as early as in the Soviet times. Having won the Komsomol Prize, he contributed a lot of his time and efforts to the youth section of the Union of Artists of Kazakhstan. He arranged young artists’ exhibitions where he used, for the first time then, advertising and design approaches. I remember myself awestruck by a huge papier-m?ch? apple hanging at the entrance to an exhibition hall. He was the first to organise a plein-air session in Tau Turgen where many artists created works that later became classics of Kazakh art. These included The Four Prophets by Bakhyt Bapishev and Asya’s Golden Dream by Yelena Rudoplavova. He supported the first exhibitions of Eduard Kazarian, Yelena Vorobyeva, Askar Yesdaulet, Andrei Noda, Almagul Menlibayeva, Galym Maidanov and other artists who were very young at that time.

In 1987, Yerbolat painted The Silk Way, the composition and colours of which reminded of the canonic Harrowing of Hell, and Kokpar, which Bayan Barmankulova, in her article Archetypes in Kazakh Art, associated with young people’s uprising at the New Square in Almaty. Later, Yerbolat tried persistently to make me a member of the youth section of the Union of Artists until, in 1990, I told him that we were too old already for that.

The Soviet Union broke down the very next year.

Valeria IBRAYEVA